JUVET LANDSCAPE HOTEL

|

|

If you really want to get away from it all, try the Juvet Landscape Hotel near Alsted in west Norway. Tourists are drawn to this remote spot by the Reinheimen National Park, a sublime tableau of mountains and forests, with a famous waterfall set in a deep ravine.

Knut Slinning established a hotel here by renovating old farm buildings near the ravine. He also commissioned the Oslo-based partnership of Jensen & Skodvin to provide new accommodation on the site. Now in their late forties, Jan Olav Jensen and Børre Skodvin were highly commended in the AR Awards for Emerging Architecture for a church at Mortensrud (AR December 2002). Connecting with nature but still unsentimentally of its time, their work draws deeply on the Norwegian modernist tradition of Sverre Fehn (see page 24). More recently, a convent on the Norwegian island of Tautra astutely explores the interaction between the man-made, spiritual and natural worlds.

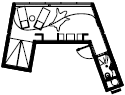

In terms of form and programme, the hotel is a much simpler proposition, but with a thoughtful twist. Rather than construct a large, intrusive single building, the architects hive off the individual rooms into seven self-contained cabins dispersed around the thickly wooded site. Careful orientation and space planning ensures that none of the cabins directly overlook each other. Each has its own view of the landscape so, to some extent, guests can pretend that it’s just them and the great outdoors.

Despite the bucolic setting, Jensen & Skodvin forsakes folksy rusticity in favour of a more minimal, Miesian aesthetic. Each cabin is an exquisitely simple single-storey box clad in strips of Norwegian larch. As they are intended only for use during the summer, walls are uninsulated. Floor-to-ceiling glazing is set against slim frames of standard steel profiles and stepped edges extend the external layer of glass to the corners. Cabins accommodate two people and, though similar in size, each has a slightly varied living room and sleeping area, with a bathroom contained in a narrow leg plugged in to the main volume. The crisply detailed larch and glass containers form a taut counterpoint to the dreamy luxuriance of the landscape.

To impact lightly on the site, cabins sit on platforms supported by 40mm diameter steel foundation rods drilled into the rock. This causes minimal disruption to the existing topography and vegetation, a fact that the architects are keen to emphasise, both as a practical response to the site and as a contribution to wider notions of sustainable building. ‘Conservation of topography is an aspect of sustainability that deserves attention,’ explains Jensen, dismayed at how most construction usually involves the obliteration or modification of the existing terrain. ‘Conserving the site is a way to respect the fact that nature precedes and succeeds man,’ says Skodvin. ‘Observation of the topography also highlights the irregularities of the natural site, explaining both itself and its context with more power.’

cabins touch the ground lightly and defer to the landscape

Cabins are clad in thin strips of larch

within touching distance

A TAUT COUNTERPOINT To tHE DREAMY

LUXURIANCE OF THE LANDSCAPE

Currently have 0 comments: